Onions—pounds and pounds of onions, both yellow and red—form the foundation of most Ethiopian dishes. They are usually ground or minced and cooked down very slowly to extract as much flavor as possible. Zenash begins her preparations with a huge brazier filled with 25 pounds of them. She stirs this mountain with an oar, until it forms a thick, copper paste. In addition to the complex, unctuous flavor, the onion paste gives a special texture and weight to sauces and stews.

To the onions, Zenash adds another layer of flavor with minced ginger and garlic. Finally, freshly toasted and ground spices are incorporated into the mix. Chili powder, paprika, allspice, clove, cinnamon, turmeric, fenugreek, cardamom, cumin, and nigella seeds are all used in different combinations. A spice shop makes Zenash’s special blend, her personal mixture for berbere. When added to the base of onion, ginger, and garlic, this combination forms the foundation for wots, a large category of stews that are bolstered with legumes, vegetables, or meat.

In addition to berbere, Zenash always has another building block in her kitchen known as niter kibbeh, spice-infused clarified butter. It is used both as a base and as a final touch that provides richness and visible shine to dishes.

Zenash’s food uses lots of fresh vegetables—cabbage, carrots, leafy greens, bell peppers, zucchini, tomatoes, and jalapeño peppers. Chickpeas, favas, lentils, and shiro, a flour made from dried legumes and spices, are always on the menu. She uses a variety of grains, including tef, red wheat, barley and oatmeal. Much of her food is vegetarian, but Ethiopians love meat as well, so chicken, lamb, and beef are also featured on the menu.

Injera, the flatbread made from a fermented batter featuring the high protein grain tef, is a staple at Ras Dashen. It is prepared every day on a 16-inch nonstick electric griddle. Injera is spongy, thin, like a French crepe, and has a uniquely sour taste. It is prized for its pockmarks, or eyes, that dot the surface of the bread and allow it to soak up the juices from the many sauces and stews. From her start selling food in America 36 years ago, Zenash has kept that first batch of fermenting yeast alive, every night contributing to the next day’s batch of bread.

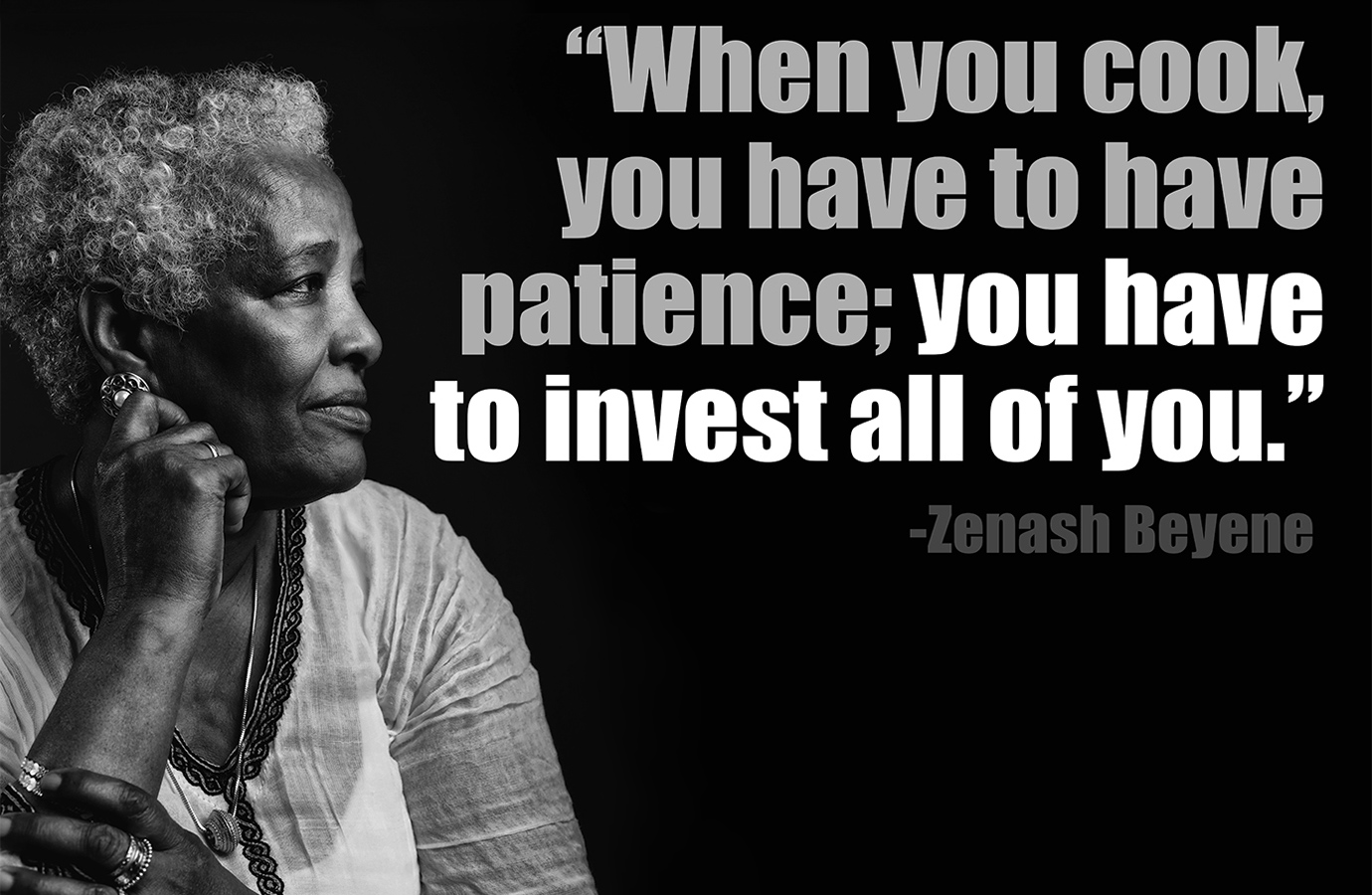

Zenash tells me that recipe-books are not a part of Ethiopian culture. Cooking is learned from your mother and her extended family of relatives and friends. Preparations are labor intensive and often require a group effort. The many hours spent in the kitchen are a communal experience just as the meal is traditionally enjoyed with a group of family and friends.

I had the good fortune of watching Zenash in her restaurant kitchen. In the few recipes provided here, I have made my best guess as to the quantities she used. The recipes are only meant to be an introduction to the world of Ethiopian cuisine.

Recipes

Niter Kebbeh (Clarified spiced butter)

Berebere Seasoning Paste (Onion, garlic and ginger paste with spice)

Thank you for writing the gazette. The articles and recipes make me stop and pause about the sustanance of food throughout the history of time. Your passion seems more than discussing the nutrients of food but it speaks to the nutrients of the soul. The stories and recipes should be discussed in college classrooms. I admire and respect your passion.

Drooling…