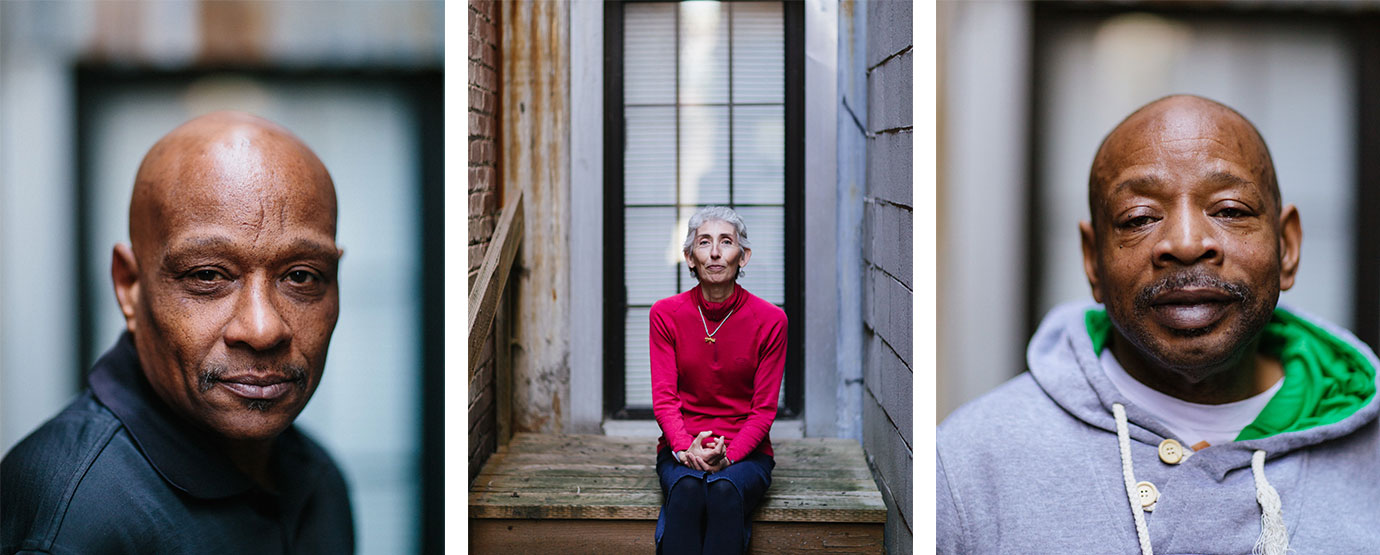

The kitchen saved my life and I’ve seen it save other people.

Chef Phoebe Sanders

Food gives life in more than one way. Not only in the traditional way of providing nutrients to our body. The preparing of food can also give purpose to the lives of people who have been ignored by most of society and now have dignity through work that matters to others.

Wesley Verhoeve, photographer

From 2005 to 2007, I ran the Community Kitchen Program at the Greater Chicago Food Depository. We produced 2,500 meals a day for kids in after-school programs. The kitchen also functioned as a twelve-week culinary training program for entry-level positions in the food industry, for the dishwashers, prep cooks, stock boys, lunch ladies, and back-waiters that are the backbone of the industry. Some of these trainees had just been released from prison, where they often had worked in kitchens while serving time. Some were trying to recover from the ravages of addiction and homelessness. Others were trying to get into the workforce after a lifelong pattern of unemployment.

Ten years have passed since that job, but a photo essay published on the website Exposure sent me back to this period of my life in the kitchen. Wesley Verhoeve’s portraits capture something essential about the people and the instructors in Episcopal Community Services’ CHEFS program (Conquering Homelessness through Employment in Food Services) in San Francisco. Like the Food Depository, CHEFS is a culinary training program that provides instruction in the technical and professional skills needed for entry-level jobs.

Currently in its 19th year, the program has been running since 1997. People are eligible to participate if they live on the street, in transitional housing, or if their income is below the poverty line as defined by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The five-month program is separated into three phases. In Phase 1, participants learn basic employment and kitchen skills. In Phase 2, the focus is on food production. Participants do the basic prep work for the 1,000-plus daily meals served at the two ECS shelters and for their seniors’ program. There, 100 three-course meals are prepared in their entirety every day. The program culminates in Phase 3, with an eight-week internship at a variety of San Francisco restaurants and corporate kitchens.

While the CHEFS program has an attrition rate of 50%, about 25 to 30 students will graduate every year. Moving from homelessness to a rigorous kitchen setting can be a challenge and when someone drops out, they are given a chance to reapply. Counselors help them examine the barriers to success that they faced while in the program and explore ways to surmount them the next time around. Of the graduates, an average of 80% of the trainees regularly find jobs and an impressive 100% of the last class found employment.

Although I live in Chicago, after seeing Verhoeve’s portraits, I had to learn more about the CHEFS program, the teachers, and the participants. Fortunately, a former colleague from the Greater Chicago Food Depository, Annie Lionberger, is now living in Oakland getting her doctorate in public health. At my request, she visited the program and interviewed chef instructors and trainees. She was able to get the recipes for two dishes she enjoyed at lunch at the CHEFS’ kitchen; cioppino, the famous San Francisco fish stew of Portuguese descent, and a sunchoke-apple salad.

Following are some excerts from her interviews.

“The kitchen has always been a sanctuary for Chef Phoebe Sanders, the program manager at CHEFS. As a child, whenever she moved, she quickly made the kitchen her shelter, preparing all the family’s meals. In high school and college, she got jobs in restaurants, working her way up from hostess to line cook. Years later, after leaving an abusive relationship and moving to a domestic violence shelter, she tried to envision a more positive future. As she began her new life, Phoebe realized that two things were non-negotiable: being in a kitchen and working at the intersection of food service and social justice.”

“After graduating from culinary school, she worked as a caterer in San Francisco’s competitive private chef market. She became a cheese-monger. To pursue the other part of her dream, she started volunteering as an instructor at CHEFS, where she used cheese to teach students about analyzing flavor. In 2013, she was hired as a chef-instructor, and this past May she was promoted to Program Manager.”

“Phoebe witnesses the restorative power of the kitchen everyday. Take Maggie, a 50-something year-old woman currently in Phase 2 of the program. A mother and former schoolteacher, she served eight years in prison after causing a car accident that resulted in the death of the other driver. When she was released from jail this past spring, she didn’t have much hope for her future. However, while living in a local shelter, Maggie—a self-proclaimed foodie—heard about CHEFS. It was a Friday, and the new cohort was starting the following Monday. Maggie rushed in her paperwork and was admitted into the program.”

“At first she didn’t know what to expect. She felt lost. But now Maggie’s enthusiasm about CHEFS and about her future are contagious. Only eleven weeks into the program, she feels she has a new lease on life. She walks into a room with confidence, a stark contrast to her behavior in the first few weeks of the program. She is excited about her future and the journey ahead of her, which she is certain will include both cooking and being of service to others. The kitchen is Maggie’s redemption.”

–Annie Lionberger

As these stories attest, CHEFS offers people who often don’t get a second chance an opportunity to refresh their lives. The door always remains open for graduates to stay connected to the program and to receive continued employment support, but long-term connection with many graduates remains an elusive goal. Securing job placements is relatively easy, given the constant turnover in the industry, and CHEFS aspires to learn how well its alumni retain and progress in their employment one year or longer from graduation.

Still, evaluating a program’s success by looking solely at employment figures doesn’t tell the whole story. These training programs are often the first thing that many participants start and actually complete. Along with a new set of skills, they learn to be part of a team. They experience the joys and challenges of having coworkers with whom they might have conflicts but who can also pull them through on a bad day.

The act of cooking, providing sustenance for oneself and for others, is itself a healing experience, wherever it eventually takes people. As Chef Phoebe told Annie: “When you’re navigating the pressures of homelessness—the trauma of homelessness—to have the humanizing experience of interacting with food is really, really valuable. People can start to value themselves.”

Beautiful and timely.

We must not lose hope even in the face of impossible odds. Nurturing optimism can take many forms and can be practiced through many a different process giving birth to positive change.

Thanks for bringing those stories to light.

Beautiful reminder. Thank you Fadia and LISA!

I’m extremely pleased to uncover this website.

I want to to thank you for your time for this particularly wonderful read!!

I definitely really liked every part of it and I have you

saved to fav to see new information on your website.

Thanks so much for your enthusiasm! I look forward to hearing more from you. Cheers, Lisa

Loved reading this, and agree wholeheartedly with the comment above from Fadia. It’s inspiring to hear about the CHEFS program. Such a good reminder of human resilience, and the possibilities that can emerge even under the most trying circumstances. The last quote from Chef Phoebe was poetry, so beautifully articulated. Thanks for writing this!

Thanks so much for your response to this edition of the Gazette!