A short walk from my house is a commercial strip with drug stores, a gym, resale shops, a Whole Foods, and a number of small restaurants. Mostly chef owned, these restaurants feature dishes that summon nostalgia from the proprietor’s childhood.

The Ethiopian restaurant Ras Dashen, named after the highest mountain in the country, has been a presence on the street since 2001. Almost every morning, I walk past the restaurant and inhale a swirling cloud of sweet smoke and spice: a mellow base of ginger, onion, and garlic—spikes of chili and cumin, maybe fenugreek? clove? cardamom? The combinations pique my interest. I have also seen the owner walking in the neighborhood, although usually I only catch a glimpse of her through the kitchen window. She has a regal bearing, a beautiful woman in command of her kingdom, Ras Dashen.

In 1958, Zenash Beyene was born into an Orthodox Jewish family in Ethiopia. Her family strictly adhered to the ancient customs and laws of the Torah. Beta Israel, the ancient Jewish community, kept to itself—outside contact could lead to trouble. Trouble came and Zenash was forced to flee. Cooking provided a livelihood all along that journey. But at least as important, cooking gave her a connection to the family and homeland that she was forced to leave behind.

Never ever tell someone you are a Jew, or they will kill you

Such was Zenash’s experience from early childhood. She is from Belesa, a village near the ancient capital of Gondar in the north of the country. Crimes against Jews were ignored, if not encouraged, in rural Ethiopia. Zenash’s grandfather was a prominent man in the community who owned cows, goats, horses, sheep, and mules. He was envied for his success, and eventually murdered for his wealth. Her father was a talented blacksmith and carpenter. He was deeply steeped in the Torah and was sought after for wisdom and advice from people all over the region. After his father’s murder, he refused to be silent, demanding accountability. For this, his farm and animals were torched, and he himself was eventually killed.

The family reeled from the losses. At age six, Zenash went to work with her mother. It was a hard life against the backdrop of an unforgiving environment. Mother and daughter earned a living making ceramics—large platters and bowls that fit on top of mesob, the traditional woven tables used for the enjoyment of a communal meal.

Working as a craftswoman from such an early age, Zenash gained a deep appreciation for the beauty of everyday objects. This appreciation expanded to a love of painting and music. You can enjoy this in the décor at her restaurant: marvelous paintings, well-used, traditional jebena (coffee pots), brightly colored mesob and painted trays.

Zenash’s journey is a reflection of Ethiopian politics in the early 1970s. After the emperor Haile Selassie was deposed, Marxist militias were active in the North, persecuting students, particularly Jews, for their presumed Communist affiliations. Anyone was at risk of being grabbed off the street, jailed and tortured, or simply “disappeared.”

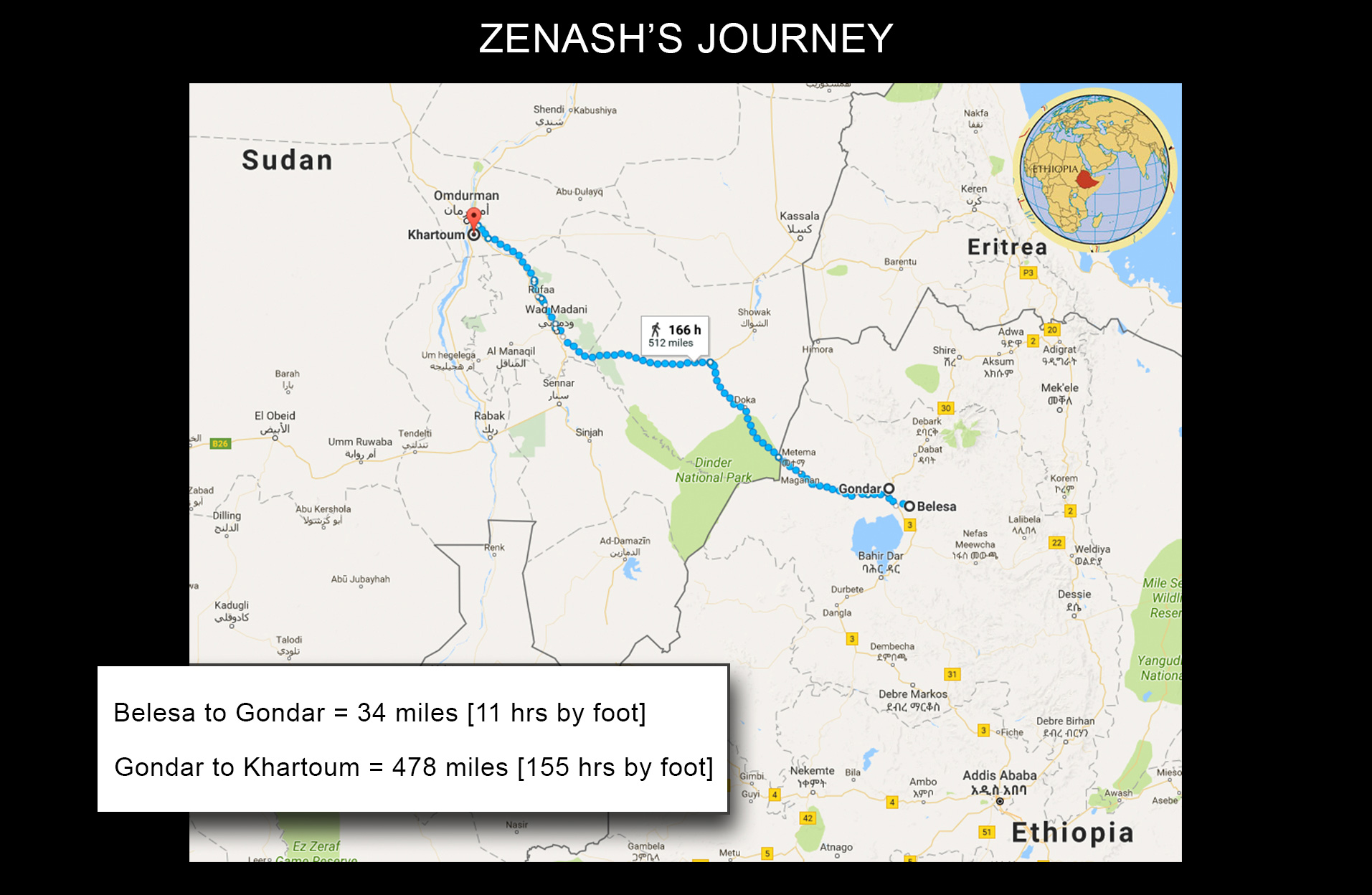

At the age of 15, Zenash left her 8-month old daughter with her mother and joined the exodus. With a group of around 40 young students, she fled on foot, first to Gondar and then to Sudan.

For a time, Zenash stayed in the capital, Khartoum, working as a housekeeper for foreigners. The pay was poor and she was always moving on. Finally, she received a passport and a two-year contract to work in Jedda, Saudi Arabia, in the household of the king’s youngest brother. The labor was brutal, “It was very bad there…really, I’m telling you—you don’t want to know.” She would not elaborate.

When her contract was finally up, she went back to Sudan and opened the first of her secret restaurants. Word of her delicious food spread quickly and before long she had three women helping her cook, four men helping her serve the customers. The local butcher needed to kill two lambs every day to feed her clientele.

Preparing the dishes that she learned as a child while cooking with her grandmother and mother was her way of cherishing these women.

“My grandmother was famous for her challah. Her bread was perfect. The dough was covered by a special leaf and cooked outside over charcoal. To have it ready on Friday, we would start on Tuesday, soaking the grains before grinding the flour…everything was done by hand—no measuring.”

In the early 1980s, the persecution of Ethiopian Jews accelerated. At the same time, the rabbinical council certified the community as one of the original “lost tribes of Israel”. A crush of people fled to Sudan, hoping to immigrate to Israel. They often arrived in Khartoum starving and dying from malaria. In one three-month period, 4,000 people perished. By 1981, Zenash felt it was imperative to leave. On November 6, sponsored by Traveler’s Aid, she landed in New York en route to Chicago.

“I came into New York at nighttime and had a window seat. Oh my God, wow, wow, wow, I could not believe all that light! I still see it.”

That first winter was brutal. Traveler’s Aid settled her into her first apartment on the north side of Chicago, in a building full of Ethiopian refugees. Shocked by the cold and the strange culture, they all longed for the familiar tastes of home.

Zenash gave herself three weeks to ferment her first batch of injera, the cherished Ethiopian flat bread made with an ancient high-protein grain called tef. She experimented with different flours available in Chicago at the time.

“I was so homesick for my injera! I cried! Tef wasn’t available then. I tried everything: red wheat, rice flour, all-purpose flour, even Aunt Jemima.”

Finally satisfied with her product, she announced to the building that her apartment was open for take-out. The halls filled with the aroma of slowly cooking onions, ginger, and garlic; toasted spices and freshly-roasted green coffee beans—smells that comforted the displaced and homesick.

Zenash moved to a bigger space and the business grew. Once again, her apartment became a secret restaurant, now open for dinners and parties. She met her husband at one of those meals. Kevin Swier came to Chicago from South Dakota for graduate school. He was living in Hyde Park, finishing a post-doctorate in biology at the University of Chicago. Along with six friends, he came to try the Ethiopian restaurant located in Zenash’s apartment. The group had a procession of dishes, and then she sat down to make coffee and converse. Kevin described the evening they met:

“All I remember is her…we talked and talked. I just remember looking at her, how I liked the way her hair curled around her ears. From that first meeting, there was something—at least for me! We met in 1993 and married in January 1995. In 2001 we opened Ras Dashen, eight years to the day we met.”

Wedding, January 1995

Sixteen years later, they are still at the same location on Broadway. After so much time in a grueling business, the conversation turns to what’s next after the restaurant.

“For myself, I want to shop every day—everything fresh, listen to good music and cook good food. I want to enjoy my Shabbat (the Jewish Sabbath). I want to share my knowledge, share my grandmother and my mother’s cooking. I want to do my spices, my berbere, and hot sauces…put them in a jar and then I’ll be right there, in everyone’s kitchen.”

Whatever is next, I have no doubt Zenash will be successful. She comes from a long line of people with talented hands. Her life as a refugee presented many obstacles, but she has an unquenchable optimism and joie de vivre. She is kind, but can be fierce when required. With a laugh, she tells me her name means “lucky, good news.” I think of something my father used to say, “It’s amazing how lucky hardworking people are.”

Fortunately for her friends and customers, Zenash still stands facing the stove at her restaurant feeding Ethiopians, Americans and citizens of the world.

A brilliant , touching story. The photography captures the essence of Zenash. Nicely done, Lisa!

What an awesome story! Love you and proud of you Zenash!

Wonderful story. I can’t wait to visit and go to the restaurant!

It will be wonderful to be there with you! Lisa

Congratulations, Lisa, on creating a true adventure in food and living that would otherwise be inaccessible. You have opened my eyes and mind to history, geography, culture, foods, and people unknown to me. Zak Yasin’s photographs capture the essence of your story. Well done!

Great job, Lisa, on creating a true adventure in food and living that would otherwise be inaccessible. You have opened my eyes and mind to history, geography, culture, foods, and people unknown to me. Zak Yasin’s photographs capture the essence of your story. Well done!

Zenash – such a beautiful person and story of survival and thriving….and Lisa and Zak, the photos and writing are perfect and gorgeous!

Lisa – Congrats on another beautiful issue…I really enjoyed it. Zenash’s story is amazing, touching and your writing has done it justice! As always, the pictures are so inviting and I can’t wait to try the Chickpea salad…looks delicious!

Beautiful article about a beautiful person…an inspiring survivor! When we lived in the neighborhood, Ras Dashen was one of our first favorite restaurants.

Thank you for bringing this to us, Lisa. Your appreciation for the art of being and for giving is inspiring. What an amazing story to tell and food to celebrate.

This was beautifully written! Thank you, Zenash for being transparent, vulnerable, and for allowing your truth to inspire…It has deeply inspired my daughter and I. My heart aches for the depth of your sorrows experienced so young in life and yet leaps for utter joy for every overcoming victory…Victory is forever your truth. You looked to serve others in the midst of turmoil, hatred, and chaos. Wherever you have walked peace, love, and beauty followed and embraced those around you. Thank you for your heart, grace, and faithfulness. You opened a door.

Dearest Zenash: We cannot wait to have a seat at your table.

Thank you so much for these comments. I will be sending them on to Zenash! Lisa